Belle Shefrin, 9, holds a doll of Hillary Clinton while listening to Clinton speak at a campaign rally in Ohio in 2016.Brian Snyder / Reuters

Belle Shefrin, 9, holds a doll of Hillary Clinton while listening to Clinton speak at a campaign rally in Ohio in 2016.Brian Snyder / ReutersHillary Clinton may become the first female president of the United States, but she is not the first woman who has run for the job.

This year alone there are five women who have earned their party’s nomination—including the Green Party’s Jill Stein and the Party for Socialism and Liberation’s Gloria La Riva, who has been on various Socialist tickets for more than 30 years.

Although Clinton, in July, became the first woman ever to be nominated by a major political party, dozens of women have attempted the feat in the past century and a half.

Victoria Woodhull, an early suffrage leader, ran for president in 1872 on the Equal Rights Party’s ticket—decades before women had even secured the right to vote and despite the fact that, at 34, she was too young to be eligible. She’s remembered today as part-hustler, part-trailblazer, and her roster of experience included stints as a clairvoyant and a Wall Street broker. (If anyone actually voted for her, those votes were never counted.)

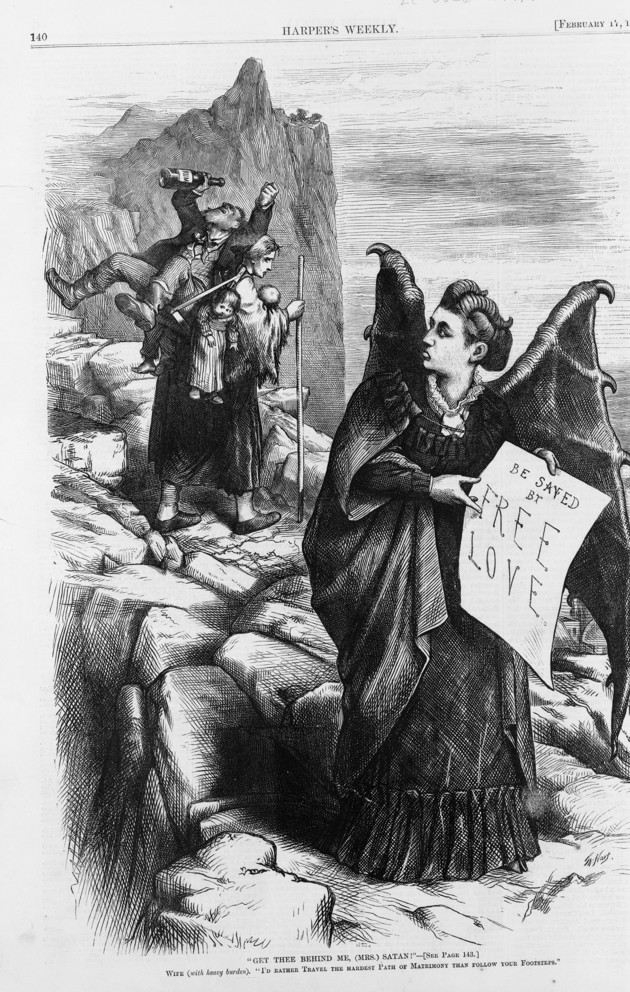

In this Harper’s Weekly cartoon, published in 1872, a woman is seen carrying her children and drunk husband. She says to a demonic portrayal of Victoria Woodhull, "I'd rather travel the hardest path of matrimony than follow your footsteps." Woodhull was an advocate for women’s right to divorce their husbands, a controversial position at the time. (Library of Congress)

Belva Ann Lockwood followed suit in 1884 and 1888, arguing that just because she couldn’t vote didn’t mean that men couldn’t vote for her.

Margaret Chase Smith, who was later a Republican candidate for U.S. president, photographed in 1943.

(Library of Congress)

In 1920, Laura Clay and Cora Wilson Stewart both sought the Democratic Party nomination. (James Cox beat them, then lost to Warren Harding.) In 1964, Fay Carpenter Swain attempted to get the Democratic nomination while Margaret Chase Smith went after the Republican nomination. (Smith lost to Barry Goldwater, who himself lost to Lyndon Johnson that year.) In 1972, a trio of Democratic women tried to land the ticket: Shirley Chisholm, Patsy Mink, and Bella Abzug. Mink, who died in 2002, is best known today as the author of Title IX. She also held the distinction of being the first Asian American to seek her party’s nomination for the presidency. George McGovern wound up winning the Democratic nomination in 1972, then suffered a stunning defeat to Richard Nixon in the general election.

It’s tempting to read something into the fact that so many women attempted to secure nominations from parties that rejected them—only for those parties to ultimately lose the election with their preferred, male nominee. But what might such a pattern suggest? It seems possible that women saw a more plausible opening for their own candidacy in elections where their parties were weaker. That, in turn, might have made an already politically risky move—to run for president as a woman—seem slightly less treacherous. Less treacherous to the public that might vote for them, that is.

To run for president at all, and especially as a woman, requires a level of boldness that all but ignores the ultimate improbability of victory.

A few years ago, I spent a rainy Saturday afternoon picking through Mink’s vast archives at the Library of Congress, and was bowled over by the sexism in the news clippings about her. One newspaper story, from her time as a Hawaii state legislator, began by describing her as “the cutest senator you ever saw.” (Things have changed for women in politics, but not as much as it sometimes seems.)

Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress, faced similar treatment. When she was first elected—and immediately relegated to an undesirable subcommittee assignment having to do with forestry—she pushed back. Here’s the Associated Press’s 1971 account of what happened:

She surprised colleagues by striding to the microphone during a Democratic caucus and refusing to budge until she was reluctantly recognized by the leadership. Then, she successfully pushed through a measure changing her assignment to veterans affairs. “There are a lot more veterans in my district than there are trees,” she said.

A male colleague told her she’d “committed political suicide.” She ignored him, ran for president anyway, then continued to serve as a member of Congress until 1983.

The year Chisholm ran for president, 1972, was something of a turning point for women and the presidency—which makes sense, given the momentum of the women’s movement and rise of second-wave feminism. Ever since, there have been women vying for at least one of the major party’s nominations (more often Democrats than Republicans) with each presidential election, a trend that seems certain to continue.

Patsy Mink, photographed in 1992. (Library of Congress)

Today, the idea that a woman might be elected president of the United States seems inevitable. It may, in fact, be mere days away.

And yet, even without having been elected, some women have played a far more prominent role in the American presidency than has often been acknowledged. Edith Wilson, the first lady to President Woodrow Wilson, was “in a very real sense the first woman president of the United States,” the writer and historian Thomas Bailey argued in 1945.

After President Wilson suffered a stroke in 1919, the first lady informally assumed the role of acting president—she described it in her memoir as serving as a “steward” for her husband. (Though there was a succession plan in place for when a president died in office, dealing with a chief executive’s prolonged disability was thornier.) All dispatches intended for the president were to go through his wife first. Edith Wilson insisted that, although she strictly controlled access to the president, he was still the one making the decisions. “I myself never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs,” she later wrote. “The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.”

Historians have since come to see Wilson’s stewardship slightly differently: According to her White House Historical Association biography, Edith Wilson was “functionally running the Executive branch of government for the remainder of Wilson's second term.

No comments:

Post a Comment