Bill Clinton with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat at the White House in 1993

Bill Clinton with Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat at the White House in 1993

Getting Bill Out of the House.If Hillary Clinton takes office, her best adviser in mediating Israel and Palestine’s century-old conflict might be the man who came closest to doing it before by Jeffery Goldberg ( republished with permission of the author and The Atlantic ( magazine)).

Bill Clinton was a president singularly taken by the idea that making peace between Palestinians and Israelis was possible. He devoted a disproportionate amount of time and political capital to the search for a solution to the conflict. Even before the man he describes as his hero, Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli general turned prime minister, was assassinated in 1995, Clinton believed that he had been called to this cause. Uniting the children of Isaac and Ishmael, the warring sons of Abraham, was, for a Southern Baptist, too tempting a challenge to ignore. In 2000, he managed to bring the two sides close—infuriatingly close, in retrospect—to a final status agreement. But the two-week summit at Camp David that July, and subsequent rounds of negotiations between the Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, and the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, failed to close the remaining gaps. In his very last weeks in office, Clinton was still trying for an agreement, presenting a set of ideas that came to be known as the Clinton Parameters, which set the framework for a final push. The Israelis accepted them, with reservations.

As Clinton later wrote in his memoir:

But Arafat would not, or could not, bring an end to the conflict. “I still didn’t believe Arafat would make such a colossal mistake,” Clinton wrote. “The deal was so good I couldn’t believe anyone would be foolish enough to let it go.” But the moment slipped away. “Arafat never said no; he just couldn’t bring himself to say yes.” In one of their last phone conversations, shortly before Clinton’s term ended, Arafat told the soon-to-be ex-president, in his comically ingratiating manner, that he considered him a “great man.” Clinton responded coldly: “I am not a great man. I am a failure, and you have made me one.”

This was an exaggeration. No one has come closer to achieving peace than Clinton, and it is at least somewhat plausible that, had Rabin lived, and had the Palestinians been led by someone other than Arafat, Clinton would today be known as the man who brought an end to the Middle East’s 100‑year war. He also would almost certainly belong to an elite club, composed of the other senior-most living Democrats—Jimmy Carter, Al Gore, and Barack Obama—all of whom are recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize. Exclusion from this group cannot please such a competitive man.

And yet no one I’ve encountered believes that Clinton pursued peace merely for acclaim. People who know him say he remains preoccupied with the issue today. “This is unfinished business for him,” Clinton’s former Middle East negotiator, Dennis Ross, told me. In particular, Clinton is said to be troubled that he could not achieve for the martyred Rabin what Rabin had tried to achieve himself.

Sometimes, however, life provides second chances.

I recognize that what I’m about to propose will seem presumptuous. But I believe that events may be organizing themselves in such a way as to provide Bill Clinton with one more mission. If elected, his wife will, like all other presidents of the past 40 years, at some point probably find it necessary, or advisable, or even desirable, to attempt to solve the unsolvable conflict. She would have her choice of negotiators, but the only living person the antagonists would find, to their chagrin, impossible to ignore is Bill Clinton, a figure of singular stature in the Middle East. President Obama, after intermittent and tactically flawed attempts to ignite the peace process, has alienated many Israelis and disappointed many Palestinians. Bill Clinton, however, is the sui generis president who left office widely popular on both sides of the divide. Assigning Bill the role of super-negotiator (deputies would have to lay the groundwork for a revived process, and manage its numberless intricacies) could provide Hillary with her best chance of success.

Assigning Bill this task could also take care of another potential problem for Hillary: a pressing need to get him out of the house.

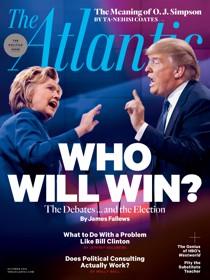

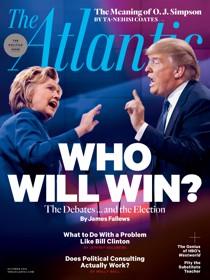

FROM OUR OCTOBER 2016 ISSUE

Try 2 FREE issues of The AtlanticSUBSCRIBE

I am writing this article in the courtyard of East Jerusalem’s American Colony Hotel, one of the loveliest places on Earth, and an epicenter of intrigue during the glory days of the peace process, in the 1990s. Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, set himself up here during his lengthy, unsuccessful term as a Middle East peace negotiator starting in 2007. There’s no reason the U.S. government couldn’t rent much of the place out for Bill Clinton. I think he would enjoy it very much, and my guess is that Hillary, and in particular her top aides, might enjoy having him here as well.

Now to the assumptions built into this idea. Leave aside the most obvious of these—that Hillary Clinton will win the presidency, and that Bill Clinton could be persuaded to devote himself once again to this frustrating, exhausting work. (It is one thing to consider the cause of peace unfinished business; it is another to want to finish the business yourself.)

One salient assumption is that the Bill Clinton of today remains the Bill Clinton of 16 years ago. Clinton has just turned 70, and he has seemed, from time to time on the campaign trail, wan and unfocused. Peace negotiations require, as a prerequisite, large reservoirs of stamina. So his capacities are worth questioning.

Another assumption has to do with the evolving nature of the conflict, and of the efforts to end it. The peace process is hovering near death. Twenty-five years after George H. W. Bush gathered Israelis and Palestinians (and others) at the Madrid peace conference, the prospects for a two-state solution seem more remote than ever. Each of the plans formulated to restart the process has been very nearly doomed to fail. John Kerry, Obama’s energetic secretary of state, has wasted a great deal of time in recent years trying to move Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, and Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, in the direction of meaningful negotiations.

Alas, a two-state solution is the only solution. An often-discussed alternative, a “one-state solution,” is a formula for endless war and mass violence. Binational states barely work in Europe; in the Middle East, attempting to force these two warring tribes to share power would result in catastrophe. A two-state solution, on the other hand, grants the Palestinians something of what they say they want, and allows a smaller Israel to remain a Jewish-majority democracy. Both sides would be reasonably unhappy with such an outcome—a state of affairs that, in the context of the Middle East, would represent a transcendent victory.Carter, Gore, and Obama have all won the Nobel Peace Prize. Exclusion cannot please Clinton.

Any new American effort to end this conflict must be conceived of as a regional strategy, and as a bottom-up, rather than top-down, process. Today, many Arab states find themselves in tacit alignment with Israel against Iran, and against Islamic State–style extremism. A revived push would have to take advantage of this new order, and use the Arabs to lever the Palestinians into negotiations. A man of Clinton’s persuasive powers could conceivably organize such a complicated process. A man of his political gifts could also do the indispensable work of creating the conditions on the ground that would allow for an actual negotiation. This means promoting Palestinian economic independence, and it means making sure that gestures toward the Palestinians will be understood by Israelis as being in their own best interests.

The next Middle East peace negotiator will need to win the trust of the Israelis, and to fend off attacks by the Israeli right. Obama failed at this; Bill Clinton could succeed. It is a cliché in Israel to say that if Bill Clinton ran for prime minister, he would win easily. Benjamin Netanyahu’s manipulations won’t work as easily on him as they did on Obama.

There would be a certain irony in the appointment. Should Hillary Clinton be elected, her husband would be her most important adviser, but this would not be the most vital matter she could assign him to manage. This would not even be the most vital problem she would face in the Middle East. Since the revolutions of the Arab Spring, U.S. policy makers, previously enamored of the idea that solving the Israeli-Arab problem would yield solutions to all other regional problems, have come to see the dispute as somewhat marginal to core American security interests. At this point, it is perhaps the seventh-most-urgent situation in the Middle East—much less of a crisis than the cataclysm in Syria, the disintegration of Libya, the chaos in Iraq, the war in Yemen, the broader threat posed by the Islamic State, or the overarching conflict between Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

And yet, the issue has captured the world’s imagination for decades. The future of Israel has been a key bipartisan concern for generations of Americans, and it is almost axiomatic that if the Palestinians have no viable future, neither does Israel. Only the United States has the power to cajole, manipulate, pressure, and persuade these two peoples to come to an agreement, and in the United States today, the best person to lead such an effort is the person who has already led such an effort. Bill Clinton might not succeed in bringing peace—chances are good that he wouldn’t—but it would be a crime not to give it one more try.

Bill Clinton was a president singularly taken by the idea that making peace between Palestinians and Israelis was possible. He devoted a disproportionate amount of time and political capital to the search for a solution to the conflict. Even before the man he describes as his hero, Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli general turned prime minister, was assassinated in 1995, Clinton believed that he had been called to this cause. Uniting the children of Isaac and Ishmael, the warring sons of Abraham, was, for a Southern Baptist, too tempting a challenge to ignore. In 2000, he managed to bring the two sides close—infuriatingly close, in retrospect—to a final status agreement. But the two-week summit at Camp David that July, and subsequent rounds of negotiations between the Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, and the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, failed to close the remaining gaps. In his very last weeks in office, Clinton was still trying for an agreement, presenting a set of ideas that came to be known as the Clinton Parameters, which set the framework for a final push. The Israelis accepted them, with reservations.

As Clinton later wrote in his memoir:

It was historic: an Israeli government had said that to get peace, there would be a Palestinian state in roughly 97 percent of the West Bank, counting the [land] swap, and all of Gaza, where Israel also had settlements. The ball was in Arafat’s court.

But Arafat would not, or could not, bring an end to the conflict. “I still didn’t believe Arafat would make such a colossal mistake,” Clinton wrote. “The deal was so good I couldn’t believe anyone would be foolish enough to let it go.” But the moment slipped away. “Arafat never said no; he just couldn’t bring himself to say yes.” In one of their last phone conversations, shortly before Clinton’s term ended, Arafat told the soon-to-be ex-president, in his comically ingratiating manner, that he considered him a “great man.” Clinton responded coldly: “I am not a great man. I am a failure, and you have made me one.”

This was an exaggeration. No one has come closer to achieving peace than Clinton, and it is at least somewhat plausible that, had Rabin lived, and had the Palestinians been led by someone other than Arafat, Clinton would today be known as the man who brought an end to the Middle East’s 100‑year war. He also would almost certainly belong to an elite club, composed of the other senior-most living Democrats—Jimmy Carter, Al Gore, and Barack Obama—all of whom are recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize. Exclusion from this group cannot please such a competitive man.

And yet no one I’ve encountered believes that Clinton pursued peace merely for acclaim. People who know him say he remains preoccupied with the issue today. “This is unfinished business for him,” Clinton’s former Middle East negotiator, Dennis Ross, told me. In particular, Clinton is said to be troubled that he could not achieve for the martyred Rabin what Rabin had tried to achieve himself.

Sometimes, however, life provides second chances.

I recognize that what I’m about to propose will seem presumptuous. But I believe that events may be organizing themselves in such a way as to provide Bill Clinton with one more mission. If elected, his wife will, like all other presidents of the past 40 years, at some point probably find it necessary, or advisable, or even desirable, to attempt to solve the unsolvable conflict. She would have her choice of negotiators, but the only living person the antagonists would find, to their chagrin, impossible to ignore is Bill Clinton, a figure of singular stature in the Middle East. President Obama, after intermittent and tactically flawed attempts to ignite the peace process, has alienated many Israelis and disappointed many Palestinians. Bill Clinton, however, is the sui generis president who left office widely popular on both sides of the divide. Assigning Bill the role of super-negotiator (deputies would have to lay the groundwork for a revived process, and manage its numberless intricacies) could provide Hillary with her best chance of success.

Assigning Bill this task could also take care of another potential problem for Hillary: a pressing need to get him out of the house.

FROM OUR OCTOBER 2016 ISSUE

Try 2 FREE issues of The AtlanticSUBSCRIBE

I am writing this article in the courtyard of East Jerusalem’s American Colony Hotel, one of the loveliest places on Earth, and an epicenter of intrigue during the glory days of the peace process, in the 1990s. Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, set himself up here during his lengthy, unsuccessful term as a Middle East peace negotiator starting in 2007. There’s no reason the U.S. government couldn’t rent much of the place out for Bill Clinton. I think he would enjoy it very much, and my guess is that Hillary, and in particular her top aides, might enjoy having him here as well.

Now to the assumptions built into this idea. Leave aside the most obvious of these—that Hillary Clinton will win the presidency, and that Bill Clinton could be persuaded to devote himself once again to this frustrating, exhausting work. (It is one thing to consider the cause of peace unfinished business; it is another to want to finish the business yourself.)

One salient assumption is that the Bill Clinton of today remains the Bill Clinton of 16 years ago. Clinton has just turned 70, and he has seemed, from time to time on the campaign trail, wan and unfocused. Peace negotiations require, as a prerequisite, large reservoirs of stamina. So his capacities are worth questioning.

Another assumption has to do with the evolving nature of the conflict, and of the efforts to end it. The peace process is hovering near death. Twenty-five years after George H. W. Bush gathered Israelis and Palestinians (and others) at the Madrid peace conference, the prospects for a two-state solution seem more remote than ever. Each of the plans formulated to restart the process has been very nearly doomed to fail. John Kerry, Obama’s energetic secretary of state, has wasted a great deal of time in recent years trying to move Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, and Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president, in the direction of meaningful negotiations.

Alas, a two-state solution is the only solution. An often-discussed alternative, a “one-state solution,” is a formula for endless war and mass violence. Binational states barely work in Europe; in the Middle East, attempting to force these two warring tribes to share power would result in catastrophe. A two-state solution, on the other hand, grants the Palestinians something of what they say they want, and allows a smaller Israel to remain a Jewish-majority democracy. Both sides would be reasonably unhappy with such an outcome—a state of affairs that, in the context of the Middle East, would represent a transcendent victory.Carter, Gore, and Obama have all won the Nobel Peace Prize. Exclusion cannot please Clinton.

Any new American effort to end this conflict must be conceived of as a regional strategy, and as a bottom-up, rather than top-down, process. Today, many Arab states find themselves in tacit alignment with Israel against Iran, and against Islamic State–style extremism. A revived push would have to take advantage of this new order, and use the Arabs to lever the Palestinians into negotiations. A man of Clinton’s persuasive powers could conceivably organize such a complicated process. A man of his political gifts could also do the indispensable work of creating the conditions on the ground that would allow for an actual negotiation. This means promoting Palestinian economic independence, and it means making sure that gestures toward the Palestinians will be understood by Israelis as being in their own best interests.

The next Middle East peace negotiator will need to win the trust of the Israelis, and to fend off attacks by the Israeli right. Obama failed at this; Bill Clinton could succeed. It is a cliché in Israel to say that if Bill Clinton ran for prime minister, he would win easily. Benjamin Netanyahu’s manipulations won’t work as easily on him as they did on Obama.

There would be a certain irony in the appointment. Should Hillary Clinton be elected, her husband would be her most important adviser, but this would not be the most vital matter she could assign him to manage. This would not even be the most vital problem she would face in the Middle East. Since the revolutions of the Arab Spring, U.S. policy makers, previously enamored of the idea that solving the Israeli-Arab problem would yield solutions to all other regional problems, have come to see the dispute as somewhat marginal to core American security interests. At this point, it is perhaps the seventh-most-urgent situation in the Middle East—much less of a crisis than the cataclysm in Syria, the disintegration of Libya, the chaos in Iraq, the war in Yemen, the broader threat posed by the Islamic State, or the overarching conflict between Sunni and Shiite Muslims.

And yet, the issue has captured the world’s imagination for decades. The future of Israel has been a key bipartisan concern for generations of Americans, and it is almost axiomatic that if the Palestinians have no viable future, neither does Israel. Only the United States has the power to cajole, manipulate, pressure, and persuade these two peoples to come to an agreement, and in the United States today, the best person to lead such an effort is the person who has already led such an effort. Bill Clinton might not succeed in bringing peace—chances are good that he wouldn’t—but it would be a crime not to give it one more try.

No comments:

Post a Comment